A History of Falconry

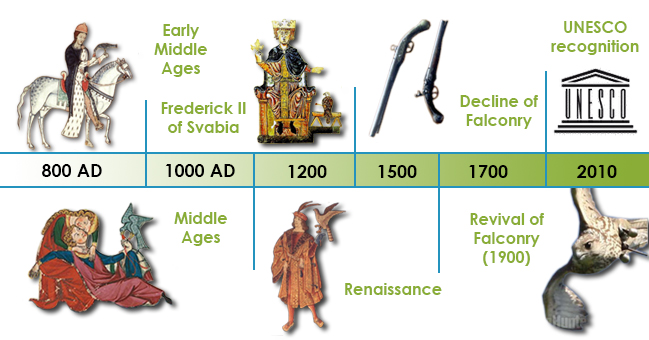

The earliest evidence of falconry in Europe is usually considered to be from the 5th century AD, written quotations from Paulinus of Pella and Sidonius Apollinaris in France and the famous mosaics in the Falconer’s Villa in Argos (Greece). For over a thousand years, falconry was extremely popular in Europe and carried enormous cultural and social capital. A marker of high social status, falconry was considered an essential part of a gentleman’s education, for it was thought to prevent sickness and damnation and demanded the cultivation of personal qualities such as patience, endurance and skill.

Using the term ‘European’ falconry is in one sense misleading, because falconry techniques and technologies have been traded across European and other countries for centuries. For example, in the thirteenth century, Arab falconry techniques were imported into Europe through Spain and through the court of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in Sicily. He employed Arab, English, Spanish, German and Italian falconers, and translated important Arab falconry works. His masterwork “De arte venandi cum avibus” distils the falconry knowledge of many cultures.

Falconry was a means of cultural communication, because its symbolic system was shared between most cultures of the known world and falcons made ideal diplomatic gifts. Its geographical reach was extraordinary. Seventeenth century falcon-traders brought falcons to the French Court from Flanders, Germany, Russia, Switzerland, Norway, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Spain, Turkey, Alexandria, the Barbary States, and India. Falconry wasn’t merely an amusement; it was a fierce articulation of social and political power; a deadly serious pastime, considered among the finest of all earthly pursuits – and big business.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the use of falcons as diplomatic gifts gradually faded, and falconry’s connection with nobility won it no favours after the French Revolution. It faded away in favour of the new sport of shooting. By the nineteenth century, only a very few individuals still practised the sport in Europe. Now falconry clubs became necessary not simply to maintain both the social traditions of falconry, but the knowledge of falconry itself.

Somehow, falconry’s living tradition survived with just sufficient falconers to pass on their treasured knowledge. Falconry had a renaissance in most European countries in the 1920s and 1930s and its popularity increased further in the 1950s and 1960s.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, much of falconry’s intangible heritage was safeguarded by what UNESCO calls living treasures – proficient falconers who could teach apprentices not only the practical methods of falconry, but also its intangible dimensions. They communicated the ethical codes of falconry sportsmanship and could instil in their pupils an awareness of the emotional bonds falconers have with their falcons, quarry and hawking land.

Falconry in Spain and Portugal

Spain and Portugal. Recent exiting discoveries of images from the 3rd century BC in Eastern Spain, that show falconry scenes, are currently under scrutiny by academics. Until these were found scholars believed falconry entered Spain in the 5th century AD, coming from North Africa with the Moorish Kings and along the northern Mediterranean coast from Eastern Europe with the Goths at approximately the same time. Much of the history of pre-16th century Iberian Falconry is intertwined with Arab falconry of the time and written references abound in the Arabic language, for example in the 10th century.

Calendar of Cordoba and from Abd al-Yalil ibn Wahbaun in the 11th century. There are Islamic falconry images like the Leyre Chest. (1004-05 A.D.) now in Pamplona Museum, and the Al-Mugira jar. (968 A.D.) now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Whereas in other parts of Western Europe many falconry terms have their origins in medieval French, in Spain and Portugal there are many terms derived from Arabic.

Old Spanish and Portuguese books on falconry are numerous and stretch from the very early “Libro de las animalias que cazan” in Spanish, 1250, through Viscount Rocabertí’s “Llibre de cetreria” in Catalan c.1390 to Diogo Fernandes Ferreira’s “Arte de caça de altaneria” 1616 in Portuguese and now in an English translation.

After a gap of two centuries, Falconry in Spain was recovered from scratch by Dr. Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in the 1950’s. Not having any practicing falconer around in Spain his sources were Spanish medieval falconry literature and foreign falconers like the late Abel Boyer of France. In 1964 de la Fuente wrote his outstanding “El Arte de Cetrería” a masterpiece and a book of great influence not only in the Spanish, but for serious falconers everywhere. Félix, known as “the friend of animals”, was one of the most popular celebrities in Spain thanks to his TV series on wildlife.

In the ‘80’s falconry started to flourish in Spain and Portugal and currently Spain is numbered in the top five falconry nations.

Falconry in Netherlands

For centuries the Netherlands was the centre of European falconry. Currently it has some very draconian laws regulating falconers; nevertheless falconry survives and thrives at a high level. The number of falconers allowed is 200 over the whole of the Netherlands and they are permitted to fly only goshawks and peregrines at quarry.

Five clubs exist, the largest two being the Nederlands Valkeniersverbond, Adriaan Mollen and the Valkerij Equipage Jacoba van Beieran. The hey-day of falconry in the Netherlands came in the first half of the 19th century when it was a hub for falcon trading and trapping.

With royal patronage from the House of Orange and participation by gentlemen falconers from Holland, England, France and elsewhere in Europe the Loo Club was founded in1839 and enjoyed a standard of “high flight” falconry at passage herons not seen since the 1600’s.

The Netherlands has two falconry-related collections: the world famous falconry museum in Valkenswaard, the 18th and 19th century centre for hawk trapping, which supplied hawks and professional falconers to the whole of Europe. There is also a globally important collection of over two hundred falconry-related books and other items in the National Library of the Netherlands, centred on a bequest in the late 1940s by Professor A. E. H. Swaen.

There is also a Falconry Historical Foundation concerned with the history of the sport.

Falconry in Belgium

Belgium, so near to Valkenswaard and the main passage routes for migrating birds of prey, also became renowned for commerce in hawks and its falconers in the early-modern period. Arendonkís falconers were renowned from the 12th century and the region of the Kempen was the homeland of Europes finest professional falconers. Some families provided falconers for about 5 centuries. Nearly all of the well-spoken, multilingual, and cultured falconers who worked for Europe ís fifteen to eighteenth-century ruling families were Flemish or Dutch.

The city of Turnhout even had a special court for falconers. The last falconmaster of the King of France in the 1880ís was a falconer from Arendonk. By the 1900s falconry had almost died out in Belgium but found a new start in 1912 with Viscount Le Hardy de Beaulieu who entertained an “Équipage” for crows and magpies led by a professional falconer till 1927. The true revival came with Charles Kruyfhooft in the late thirties. Charles was probably the last European falconer to trap passage peregrine falcons following the famous method used in Valkenswaard with a very sophisticated trapping hut. He flew crows and rooks each winter for about sixty years till his death in 1995.

By the end of the second World War there remained only three active falconers in Belgium, but by 1966 Belgian falconry had grown sufficiently for its falconers to form their own national organisation, the Club Marie de Bourgogne, named for the queen who died while hawking in 1482. Political lobbying by falconers persuaded the government to grant a limited number of licenses to keep peregrines, goshawks or sparrowhawks in order to keep the cultural heritage of falconry alive.

There are many private collections of falconry art, tapestries, books and literature in Belgium, and two small falconry collections at the chateau of Lavaux Sainte Anne and at Taxandria Museum in Turnhout. The holy falconer’s patron “Saint Bavo” was bornand lived in Belgium, he is buried in Gent.

Falconry in Ireland

In Ireland falconry was already familiar by late Celtic times (7th century on), but written references are more to the monetary value of hawks than to descriptions of the sport, pointing at an export trade rather than a native use.

Falconry was responsible for the earliest legislation protecting raptors, there are references in the Brehon Laws Ireland supplied the nobility of Western Europe with peregrines and goshawks until the end of the 19th century and the aristocracy of several nations brought their hawks there to hunt.

An Irish Hawking Club was formed in 1870 at a meeting chaired by Lord Talbot de Malahide. Maharajah Prince Duleep Singh, a familiar figure in falconry circles across two continents, pledged £50 to its founding. There has been a strong tradition of flying the sparrowhawk in Ireland and Irish falconers have enjoyed international renown.